Once upon a time, loading common scripts & styles from a public CDN like cdnjs or Google's Hosted Libraries was a 'best practice' - a great way to instantly speed up your page loads, optimize caching, and reduce costs.

Nowadays, it's become a recipe for security, privacy & stability problems, with near-zero benefit. Just last week, a security researcher showed how this could go horribly wrongopens in a new tab.

There are ways to mitigate those risks, but in practice the best solution is to avoid them entirely: self-host your content and dependencies, and then use your own caching CDN directly in front of your application instead for performance.

I'll explain what that means in a second. First though, why was this a good idea, and how has it now become such a mess?

Why was this a good idea?

The main benefit that public CDNs of popular libraries offered was shared caching. If you used a popular version of jQuery then you could reference it from a public CDN URL, and if a user had recently visited another site that used the same version of jQuery from the same CDN then it would load instantly, straight from their cache.

In effect, sites could share resources (almost always JavaScript) between one another to improve caching, reduce load times, and save bandwidth for sites and visitors.

Even in the uncached case, this still offered benefits. Browsers limitopens in a new tab the number of simultaneous open connections by domain, which limits the performance of parallel resource downloads. By using a separate domain for some resources, resource loading could be spread across more connections, improving load times for visitors.

Lastly, the main site's cookies aren't sent in requests to 3rd party domains. If you have large cookies stored for your domain, this creates a lot of unnecessary data sent in every request to your domain, again unnecessarily increasing bandwidth usage and load times (honestly I'm not sure if this overhead really had a practical impact, but it was certainly widely documentedopens in a new tab as an important 'web best practice').

Those are the abstract technical reasons. There were practical reasons too: primarily that these CDNs are offering free bandwidth, and are better equipped for static resource distribution than your servers are. They're offering to dramatically reduce your bandwidth costs, while being they're better prepared to handle sudden spikes in traffic, with servers that are more widely distributed, putting your content closer to end users and reducing latency. What's not to like?

Where did it all go wrong?

That's the idea at least. Unfortunately, since the peak of this concept (around 2016 or so), the web has changed dramatically.

Most importantly: cached content is no longer shared between domains. This is known as cache partitioning and has been the default in Chrome since October 2020 (v86), Firefox since January 2021 (v85), and Safari since 2013 (v6.1). That means if a visitor visits site A and site B, and both of them load https://public-cdn.example/my-script.js, the script will be loaded from scratch both times.

This means the primary benefit of shared public CDNs is no longer relevant for any modern browsers.

HTTP/2 has also shaken up the other benefits. By supporting parallel streams within a single connection, the benefits of spreading resources across multiple domains no longer exist. HTTP/2 also introduces header compression, so repeating a large cookie header is extremely efficient, and any possible overhead from that is no longer relevant to performance either.

This completely kills all the performance benefits of using a shared public CDN (although the cost & performance benefits of using CDNs in general remain - we'll come back to that later).

On top of the upside going away though, a lot of major downsides have appeared:

Security concerns

The security risks are the largest problem, conveniently highlighted by the disclosureopens in a new tab last week of a security vulnerability that would have allowed any attacker to remotely run code within cdnjs, potentially adding malicious code to JS libraries used by 12.7% of sites on the internet.

There are many potential routes for this kind of attack, and other CDNs like unpkg.com have been found to have similar vulnerabilitiesopens in a new tab in the past.

These kind of vulnerabilities are threats to all security on the web. Being able to inject arbitrary JavaScript directly into a tenth of the web would allow for trivial account takeovers, data theft, and further attacks on an unbelievably catastrophic scale. Because of that, large public CDNs like these are huge targets, providing potentially enormous rewards and impact against the whole web with a single breach.

While both the major CDN vulnerabilities above were found by security researchers and promptly fixed, attackers have successfullyopens in a new tab exploited specific shared 3rd party scripts elsewhere in the past, injecting crypto mining scripts into thousands of public websites in a single attack.

So far, there hasn't been a known malicious takeover of a major CDN in the same way, but it's impossible to know if the above CDN holes were ever quietly exploited in the past, and there's no guarantee that the next wave of vulnerabilities will be found by good samaritans either.

Privacy concerns

Public CDNs also create privacy risks. While online privacy was a niche topic when public CDNs first became popular, it's now become a major issue for the public at large, and a serious legal concern.

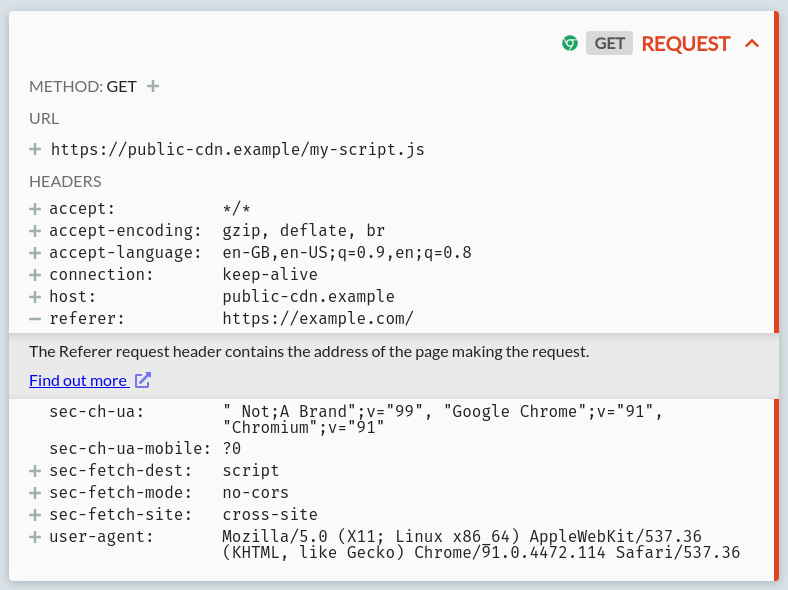

This can be problematic for public CDN usage because loading resources from a 3rd party leaks information: that the user is loading that 3rd party resource whilst on your site. Specifically, your site's domain (and historically full URL, though generally not nowadays) is sent in the Referer headeropens in a new tab with all subresource requests, like so:

At the very least, this tells the public CDN that a user at the source IP address is currently visiting the site listed in the Referer header. In some cases, it can leak more information: e.g. if a payment provider script is loaded only at checkout time, then 3rd party resource requests like this provide enough information for these CDNs to identify (by IP address and browser fingerprint) which users are purchasing from certain stores.

This is potentially a serious privacy problem, especially for public CDNs provided by companies with a clear interest in tracking users, like Google.

Reliability problems

CDNs are not infallible. They can go down entirelyopens in a new tab, become inaccessibleopens in a new tab, throw unexpected errorsopens in a new tab, timeout under loadopens in a new tab, or even serve the wrong contentopens in a new tab.

Of course, your own website can do the same too, as can any alternative infrastructure. In those cases though, you have some recourse: you can fix your site, chase the support team for the CDN service you're paying for, or switch to using a different CDN in front of your content server transparently. When your production site depends on a free public CDN, you're explicitly given zero formal guarantees or support, and you have no control of the CDN at all.

This is worse if you're worried about the long-term because no CDN will last forever. If you still have the code of your application in 20 years, but the CDN URLs used have gone away, you can't use the application anymore without lots of debugging & hunting down old copies of library files. Similarly but more immediately: if you're on an airplane, you can't reach your CDN, so doing some quick offline development is impossible.

Using a public CDN adds an extra single point of failure to your site. Now, if your servers go down or the public CDNs servers are inaccessible, everything is broken. All else being equal, it's best to keep the circle of critical dependencies small.

Performance limitations

Public CDNs as standard load every resource as a separate file, without bundling. Whilst HTTP/2 does reduce the need for bundling, this is still suboptimal for non-trivial web applications, for two reasons:

- Worse compression: HTTP response compression is always applied per response. By splitting your script across many responses, instead of compressing it all together, compression performance is reduced. This is especially true for easily compressible content that likely shares lots of common content - i.e. JavaScript files.

- No tree shaking: a public CDN must send you the entire JavaScript library in your response every time. Meanwhile, modern bundles can intelligently detect which parts of imported scripts are used through tree shakingopens in a new tab at build time, and include only those portions in your application code, which can shrink the total size of your runtime dependencies dramatically.

This is a complicated issue - there'll be times where the above doesn't apply, and it's important to measure the reality for your specific application. That said, dependency bundling is going to be faster 90% of the time and it's a reasonable default if you're building anything substantial.

What should you do instead?

Host your own dependencies, put a cache directly in front of your application, and make your application resilient to missing resources.

By hosting your own dependencies, you have control over everything your application needs, and you don't have to depend on public infrastructure. By using a cache directly in front of your site, you gain the same caching, content distribution and performance benefits of public CDNs, while keeping mitigations available for the possible downsides.

When talking about caches, I'm primarily suggesting a paid caching reverse-proxy service, like Cloudflare, Fastly, Cloudfront, Akamai, etc (although these are paid, most do have generous free tiers where you can get started or host small sites). In addition to the caching, these each offer various features on top, like DDoS protections, serverless edge workers, server-side analytics, automatic content optimization, and so on.

It's also possible to run your own caching reverse-proxy of course, but unless you're going to distribute it around hundreds of data centers globally then you're missing big parts of the performance benefit by doing so, and it's likely to be more expensive in practice anyway.

Since this caching infrastructure can cache anything, with the content itself and most caching configuration (in the form of Cache-Control headersopens in a new tab) defined by your backend server, it's also much easier to migrate between them if you do have issues. If a public hosted CDN goes down, you need to find a replacement URL that serves the exact same content, change that URL everywhere in your code and redeploy your entire application.

Meanwhile, if your caching reverse-proxy goes down, you have the option to immediately put a different caching service in front of your site, or temporarily serve static content from your servers directly, and get things working again with no code changes or backend deployments required. Your content and caching remain under your control.

Whilst this is all good, it's still sensible to ensure that your front-end is resilient to resources that fail to load. Many script dependencies are not strictly required for your web page to function. Even without CDN failures, sometimes scripts will fail to load due to poor connections, browser extensions, users disabling JavaScript or quantum fluctuations of the space-time continuum. It's best if this doesn't break anything for your users.

This isn't possible for all cases, especially in complex webapps, but minimizing the hard dependencies of your content and avoiding blocking on subresources that aren't strictly necessary where possible will improve the resilience and performance of your application for everybody (async script loadingopens in a new tab, server-side rendering & progressive enhancementopens in a new tab are your friends here).

All put together, with modern tools & services this can be an incredibly effective approach. Troy Hunt has written up a detailed exploration of how caching worksopens in a new tab for his popular Pwned Passwords site. In his case:

- 477.6GB of subresources get served from his domain every week

- Of those 476.7GB come from the cache (99.8% cache ratio)

- The site also receives 32.4 million queries to its API per week

- 32.3 million of those queries were served from the cache (99.6% cache ratio)

- The remaining API endpoints are handled by Azure's serverless functions

In total his hosting costs for this site - handling millions of daily password checks - comes in at around 3 cents per day, with the vast majority of savings over traditional architectures coming from caching the static content & API requests.

Running code on servers is slow & expensive, while serving content from caches can be extremely cheap and performant, with no public CDNs required.

Subresource Integrity

Subresource Integrity (SRI) is often mentioned in these discussions. SRI attempts to help solve some of the same problems with public CDNs without throwing them out entirely, by validating CDN content against a fixed hash to check you get the right content.

This is better than nothing, but it's still less effective than hosting and caching your own content, for a few reasons:

- SRI will block injection of malicious code by a CDN, but when it does so your site will simply fail to load that resource, potentially breaking it entirely, which isn't exactly a great result.

- You need to constantly maintain the SRI hash to match any future changes or version updates - creating a whole new way to completely break your web page.

- It doesn't protect against the privacy risks of 3rd party resources, and if anything it makes the reliability risks worse, not better, by introducing new ways that resource loading can fail.

- In many organizations, if important SRI checks started failing and broke functionality in production, unfortunately the most likely reaction to the resulting outage would be to remove the SRI hash to resolve the immediate error, defeating the entire setup.

That's not to say that SRI is useless. If you must load a resource from a 3rd party, validating its content is certainly a valuable protection! Where possible though, it's strictly better not to depend on 3rd party resources at runtime at all, and it's usually easy and cheap to do so.

Hypothetical future

A last brief tangent to finish: one technology that I do see being very promising here in future is IPFSopens in a new tab. IPFS offers a glimpse of a possible world of content-addressed hosting, where:

- All content is distributed globally, far more so than any CDN today, completely automatically.

- There is no single service that can go down to globally take out large swathes of the internet (as Fastly did just last monthopens in a new tab).

- Each piece of content is loaded entirely independently, with no reference to the referring resource and retrieved from disparate hosts, making tracking challenging.

- Content is defined by its hash, effectively baking SRI into the protocol itself, and guaranteeing content integrity at all times.

IPFS remains very new, so none of this is really practical today for production applications, and it will have its own problems in turn that don't appear until it starts to get more real-world use.

Still, if it matures and becomes widespread it could plausibly become a far better solution to static content distribution than any of today's options, and I'm excited about its future.

Caveats

Ok, ok, ok, the title is a bit sensationalist, fine. I must admit, I do actually think there's one tiny edge case where public CDNs are useful: prototyping. Being able to drop in a URL and immediately test something out is neat & valuable, and this can be very useful for small coding demos and so on.

I'm also not suggesting that this is a hard rule either, or that every site using a public CDN anywhere is a disaster. It's difficult to excise every single 3rd party resource when they're an official distribution channel for some library or if they're loaded by plugins and similar. I'm guilty of including a couple of these in this page myself, although I'm working towards getting those last few scripts removed as we speak.

Sometimes this is easier said than done, but I do firmly believe that aiming to avoid public CDNs in production applications wherever possible is a valuable goal. In any environment where you're taking development seriously enough that it's worthy of debate, it's worth taking the time to host your own content instead.

Wrapping up

Caching is hard, building high-profile websites is complicated, and the sheer quantity of users and potential sources of traffic spikes on the internet today makes everything difficult.

You clearly want to outsource as much of this hard work to others as you possibly can. However, the web has steadily evolved over the years, and public hosted CDNs are no longer the right solution.

The benefits of public CDNs are no longer relevant, and their downsides are significant, both for individual sites and the security of the web as a whole. It's best to avoid them wherever possible, primarily by self-hosting your content with a caching reverse-proxy in front, to cheaply and easily build high-performance web applications.

Have thoughts, feedback or bonus examples for any of the above? Get in touch by email or on Twitteropens in a new tab and let me know.

Want to test or debug HTTP requests, caching and errors? Intercept, inspect & mock HTTP(S) from anything to anywhere with HTTP Toolkitopens in a new tab.

Suggest changes to this pageon GitHubopens in a new tab