If you run any large public-facing website or web application on the modern web, caching your static content in a CDN or other caching service is super important.

It's also remarkably complicated and confusing.

Fortunately, the HTTP working group at the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is working to define new HTTP standards to make this better. There's been a lot of work here recently to launch two new HTTP header draft standards intended to make debugging your caching easier, and to provide more control over your cache configuration.

Let's see what that means, how these work, and why everyone developing on the web should care.

The Standards

The two proposed standards I'm talking about are:

These are designed to update HTTP standards to match the reality of the CDN-powered web that exists today, creating specifications that formalize existing practices from popular CDNs (like Fastly, Akamai & Cloudflare, all of whom have been involved in the writing the standards themselves).

Both of these are fairly new specifications: Cache-Status has completed multiple rounds of review in 2021 and is currently awaiting (since August) final review & publication as a formal RFC, while Targeted Cache-Control Headers is currently an adopted draft standard, but in its last call for feedback. In both cases, they're backed by the IETF, they're received a lot of discussion already and it's unlikely they'll change much beyond this point, but they're also still new, so support isn't likely to be widespread yet.

Why does caching matter?

If you're running a high-profile user-facing web application, caches and CDNs are absolutely critical to providing good performance for end users at a reasonable cost. Caches and CDNs sit in front of your web server, acting as a reverse proxy to ensure that:

- Content is cached, so your backend server only receives occasional requests for static content, not one request direct from every visitor.

- Content delivery is resilient to traffic spikes, because static caches scale far more easily than application servers.

- Content requests are batched, so 1000 simultaneous cache misses become just a single request to your backend.

- Content is physically distributed, so responses are delivered quickly no matter where the user is located.

If you're running a high-profile site, all of these are a strict necessity to host content on the modern web. The internet is quite popular now, and traffic spikes and latency issues only become bigger challenges as more of the world comes online.

As an example, Troy Hunt has written up a detailed exploration of how caching worksopens in a new tab for his popular Pwned Passwords site. In his case:

- 477.6GB of subresources get served from his domain every week

- Of those 476.7GB come from the cache (99.8% cache hit ratio)

- The site also receives 32.4 million queries to its API per week

- 32.3 million of those queries were served from the cache (99.6% cache ratio)

- The remaining API endpoints are handled by Azure's serverless functions

In total his hosting costs for this site - handling millions of daily password checks - comes in at around 3 cents per day. Handling that traffic all on his own servers would be expensive, and a sensible caching setup can handle this quickly, effectively & cheaply all at the same time. This is a big deal.

What's the problem?

That's all very well, but creating & debugging caching configurations isn't easy.

The main problem is that in most non-trivial examples, there's quite a few layers of caching involved in any one request path. In front of the backend servers themselves, most setups will use some kind of load balancer/API gateway/reverse proxy with its own caching built-in, behind a global CDN that provides this content to the end users from widely distributed low-latency locations. On top of that, the backend servers themselves may cache internal results, enterprises and ISPs may operate their own caching proxies, and many clients (especially web browsers) can do their own caching too (sometimes with their own additional caching layers, like Service Workers, for maximum confusion).

Each of those layers will need different caching configuration, for example browsers can cache user-specific data in some cases, but CDNs definitely should not. You also need cache invalidation to propagate through all these caches, to ensure that new content becomes visible to the end user as soon as possible.

Predicting how these layers and their unique configurations will interact is complicated, and there's many ways the result can go wrong:

- Your content doesn't get cached at all, resulting in traffic overloading your backend servers.

- Your content gets cached, but only at a lower layer, not in your distributed CDN.

- Outdated responses are preserved in your cache for longer than you expect, making it hard to update your content.

- The wrong responses get served from your cache, providing French content to Germany users or (much worse) logged in content to unauthenticated users.

- A request doesn't go through your CDN at all, and just gets served directly from your backend or reverse proxy.

- Your web site or API is cached inconsistently, serving some old & some new data, creating a Frankenstein combination of data that doesn't work at all.

This is a hot mess.

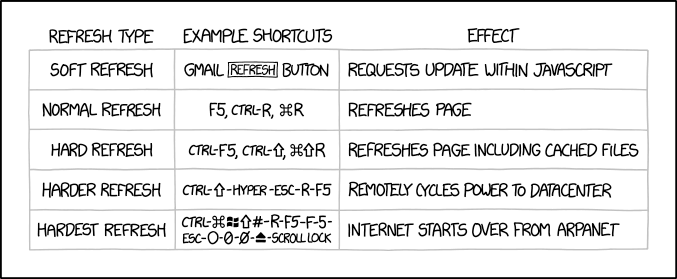

It's made worse, because lots of cache configuration lives in the request & response metadata itself, for example the Cache-Control headeropens in a new tab. This is very powerful for precise configuration, but also means that the configuration itself is passing through these layers and can be cached en route.

If you accidentally cache a single "cache this forever" response without realizing, then you can get yourself into a whole world of pain, and forcibly invalidating every layer of your caches to fix it is harder than it sounds.

How will Cache-Status help?

One of the clear problems here is traceability inside your caching system. For a given response, where did it come from and why?

Did this response come from a cache, or from the real server? If it came from a cache, which cache? For how much longer will it keep doing that? If it didn't come from a cache, why not? Was this new response stored for use later?

The Cache-Status response headeropens in a new tab provides a structure for all that information to be included in the response itself, for all CDNs and other caches that saw the request, all in one consistent format.

It looks like this:

Cache-Status: OriginCache; hit; ttl=1100, "CDN Company Here"; fwd=uri-miss;

The Cache-Status header format

The header format is:

Cache-Status: CacheName; param; param=value; param..., CacheName2; param; param...

It's a series of caches, where each one has zero or more status parameters. The caches are in response order: the first cache is the one closest to the origin server, the last cache is the one closest to the client.

It's worth being aware that responses may be saved in the cache with this header, and that that's preserved in future responses. Nonetheless, it's possible to use the parameters reading from the right to understand where this response was stored this time specifically, and where it came from previously too.

The cache-with-parameters values here are separated by commas, while the parameters themselves are separated by a semicolon (this is the sf-list and sf-item syntax from the now-standardized Structured Headers RFCopens in a new tab), and cache names can be quoted when they contain otherwise-invalid characters like spaces.

Cache-Status header parameters

To explain each cache's behaviour, there's a few parameters and values defined:

hit- the response come from this cache without a request being sent upstreamfwd=<reason>- if set, a request was sent upstream to the next layer. This comes with a reason:fwd=bypass- the cache was configured not to handle this requestfwd=method- the request must be forwarded because of the HTTP method usedfwd=uri-miss- there was no matching cached data available for the request URIfwd=vary-miss- there was matching cached data for the URI, but a header listed in the Varyopens in a new tab header didn't matchfwd=miss- there was no matching cached data available (for some other reason, e.g. if the cache isn't sure why)fwd=stale- there was matching cached data, but it's stalefwd=partial- there was matching cached data, but only for part of the response (e.g. a previous request used a Rangeopens in a new tab header)fwd=request- the request requested non-cached data (e.g. in its Cache-Control headers)

fwd-status=<status>- iffwdwas set, this is the response status that was received from the next hopstored- iffwdwas set, this indicates whether the received response was stored by the this cache for latercollapsed- iffwdwas set, this indicates whether the request was collapsed with another request (i.e. not duplicated because an equivalent request is already in process)ttl=<ttl>- for how much longer (in seconds) this response will be considered 'fresh' by this cachekey- the (implementation-specific) key for the response in this cachedetail- an extra freeform field for additional implementation-specific information

Using those, we can interpret response headers like:

Cache-Status: ExampleCache; hit; ttl=30; key=/abc

This means that the request was received by ExampleCache, which found a response in its cache (under the key /abc) and returned it, and expects to keep doing so for the next 30 seconds.

We can also examine more complicated cases, like:

Cache-Status: Nginx; hit, Cloudflare; fwd=stale; fwd-status=304; collapsed; ttl=300, BrowserCache; fwd=vary-miss; fwd-status=200; stored

(Newlines just for readability)

This means that the browser sent the request, and didn't use a cached response that it has with the same URI because a header listed in the Vary header didn't match.

The request was then received by Cloudflare, who had a matching response cached (a response with Nginx; hit, meaning it itself was a response that came from Nginx's cache) but that response was now stale.

To handle that, Cloudflare sent a request to Nginx to revalidate the response, who sent a 304 (Not Modified) response, telling Cloudflare their existing cached response was still valid. The request that was sent was collapsed, meaning that multiple requests came to Cloudflare for the same content at the same time, but only one request was sent upstream. Cloudflare is expecting to now keep serving the now-revalidated data for the next 5 minutes.

That's a lot of useful information! With some careful reading, this header alone can immediately tell you exactly where this response content came from, and how it's currently being cached along the entire request path.

(The above might sound intimidating if you're not used to debugging caching configurations, but believe me when I tell you that having this written down in one place is a million times better than trying to deduce the same information from scratch)

Cache-Status in practice

This isn't a totally new concept, but the real benefit is providing a single source of consistent data from all caches in one place.

Today, there's many existing (all slightly mismatched) headers used by each different cache provider, like Nginx's X-Cache-Statusopens in a new tab, Cloudflare's CF-Cache-Statusopens in a new tab and Fastly's X-Served-Byopens in a new tab and X-Cacheopens in a new tab. Each of these provides small parts of the information that can be included here, and each will hopefully be slowly replaced by Cache-Status in future.

Today, most major components and providers don't include Cache-Status by default, but contributors from Fastly, Akamai, Facebook and many others have been involved in the standardization process (so it's likely coming to many services & tools on the web soon) and there is progress already, from built-in support in Squidopens in a new tab and Caddy's caching handleropens in a new tab to drop-in recipes for Fastlyopens in a new tab.

This was only submitted for RFC publication in August 2021, so it's still very new, but hopefully we'll continue to see support for this expand further in the coming months. If you're developing a CDN or caching component, I'd really encourage you to adopt this to help your users with debugging (and if you're a customer of somebody who is, I'd encourage you to ask them for this!).

How will Targeted Cache-Control help?

The existing Cache-Control headeropens in a new tab was designed in a simpler time (1999). IE 4.5 had just been released, RIM was launching the very first Blackberry, and "Web 2.0" was first coined to describe the very first wave of interactive web pages. Configuring multi-layered CDN architectures to cache terabytes of data was not a major topic.

Times have changed.

The Cache-Control header defined in 1999 is a request and response header, which lets you define various caching parameters relevant to the request (what kind of cached responses you'll accept) and the response (how this response should be cached in future).

We're not really interested in request configuration here, but response cache configuration is very important. Cache-Control for responses today is defined with a list of directives that tell caches how to handle the response, like so:

Cache-Control: max-age=600, stale-while-revalidate=300, private

This means "cache this content for 10 minutes, then serve the stale content for up to 5 minutes more while you try to revalidate it, but only do this in private (single-user e.g. browser) caches".

This is a bit of a blunt instrument - the rules set here must be followed in exactly the same way by all caches that handle the request. It is possible to limit the scope of control rules to just end-user caches (with private) and in the past a few duplicated directives have been added that only apply to shared caches (CDNs etc) like s-maxage and proxy-revalidate, but you can't be any more precise or flexible than that.

This means you can't:

- Set different stale-while-revalidate lifetimes for browsers vs CDNs

- Mark a response as needing revalidation with every request in your internal caching load-balancer but not your CDN

- Enable caching with CDNs whilst telling external shared caches (like enterprise proxies) not to cache your content

This holds back a lot of advanced use cases. For most caching components, there are configuration options available to define rules within that component to handle this, but that's less flexible in its own way, making it far harder to configure different rules for different responses.

Targeted Cache-Controlopens in a new tab aims to solve this by defining new headers to set cache-control directives that target only a specific cache, not all caches.

How does Targeted Cache-Control work?

To use this, a server should set a response header format like:

<Target>-Cache-Control: param, param=value, param...

The header is prefixed with the specific target that this should apply to. The syntax is technically subtly different to the syntax used by Cache-Control, because it now uses the standard Structured Fieldsopens in a new tab format, but in practice it's mostly identical.

The target used here might be a unique service or component name, or a whole class of caches. The specification defines only one target - CDN-Cache-Control, which should apply to all distributed CDNs caches, but not other caches - but other classes can be defined later. In future you can imagine Client-Cache-Control to set rules just for caching in HTTP clients, ISP- for internet service providers, Organization- for enterprise organization caches, you name it.

To use these headers, each cache that supports them will define (fixed or user configurably) a list of targets that it matches in order of precedence. It uses the first matching <target>-Cache-Control header that's present, or the normal Cache-Control header (if there is one) if nothing more specific matches.

All in all this is pretty simple and easy to use, if you're already familiar with existing caching mechanisms. Targeted headers match certain targets, you can configure the caching rules per-target however you'd like, and the best match wins. For example:

Client-Cache-Control: must-revalidate CDN-Cache-Control: max-age=600, stale-after-revalidate=300 Squid-Cache-Control: max-age=60 Cache-Control: no-store

This says that:

- End clients (at least, those who recognize the

Client-Cache-Controlheader I've just made up) can cache this content but must revalidate it before use every time - All CDNs can cache the content for 10 minutes, and then use the stale response while revalidating it for 5 additional minutes

- Squid (a caching reverse proxy) can cache the content only for 60 seconds (and implicitly cannot use it while it's stale, since there's no

stale-while-revalidatedirective) - Anything else or anybody who doesn't understand targeted cache-control directives must never cache this content at all.

Targeted Cache-Control in practice

This is newer and earlier in the standardization process the Cache-Status, so it still might change. If you have feedback, the spec itself is on GitHub hereopens in a new tab and you can file issues in that repo (or send a message to the Working Group mailing listopens in a new tab) to share your thoughts.

That said, the spec itself is written by authors representing Fastly, Akamai and Cloudflare, so it's got good industry support already, and it's far enough through the process that it's unlikely to change drastically.

Today, both Cloudflareopens in a new tab and Akamaiopens in a new tab already support this, so if you're using those caches you can start precisely configuring both with CDN-Cache-Control, Akamai-Cache-Control and Cloudflare-CDN-Cache-Control right now. It's pretty likely that there'll be similar support in the pipeline for many other tools and services, so watch this space.

More to come

Caching in 2021 can be difficult, but Cache-Status and Targeted Cache-Control are rapidly maturing, and they're going to make it much easier to configure and debug. If you're working with caching, it's worth taking a closer look.

There are just two HTTP standards that the IETF have been working on recently - there's lots of others if you're interested in helping the web develop or learning about upcoming standards. Everything from rate-limiting headersopens in a new tab to Proxy-Statusopens in a new tab, to HTTP message digestsopens in a new tab, and HTTP client hintsopens in a new tab. HTTP is an evolving standard, and there's lots more to come! If you're interested in any of this, I'd highly recommend joining the working group mailing listopens in a new tab to keep an eye on new developments and share your feedback.

Want to test or debug HTTP requests, caching and errors? Intercept, inspect & mock HTTP(S) from anything to anywhere with HTTP Toolkitopens in a new tab.

Suggest changes to this pageon GitHubopens in a new tab