WebRTC allows two users on the web to communicate directly, sending real-time streams of video, audio & data peer-to-peer, from within a browser environment.

It's exciting tech that's rapidly maturing, already forming the backbone of a huge range of video chat, screen sharing and live collaboration tools, but also as a key technology for decentralization of web apps - providing a P2P data transport layer used by everything from WebTorrent to IPFS to Yjs.

Unfortunately though, it doesn't have the tooling ecosystem that developers used to networking with HTTP often expect. There's few supporting tools or libraries, inspecting raw traffic is hard or impossible, and mocking WebRTC traffic for automated testing is even harder. Even built-in low-level browser tools like chrome://webrtc-internals don't allow seeing messages sent on WebRTC data channels.

It's hard to build modern secure web applications on top of protocols that you can't directly see or interact with.

This doesn't just affect developers: it also seriously impacts security & privacy researchers and reverse engineers, each trying to investigate the traffic sent & received by the apps we all use. If you want to know what data a webapp you use is sending over WebRTC, right now it's very hard to find out.

Intercepting WebRTC traffic to build these tools and libraries is difficult, because unlike protocols like HTTP that were designed to allow active proxying and user-configureable PKI (i.e. CA certificates) early on, WebRTC encrypts all traffic using peer-to-peer negotiated certificates for authentication without PKI, communicates in a wide variety of different negotiated ways at the network level to avoid NAT issues, and offers no convenient APIs to configure this for debugging. All of this provides some great features to the protocol as a user, but some serious challenges when building developer tools.

As it turns out though, despite this, there are just enough places where we can hook into that it is possible to do MitM interception on WebRTC traffic. When we control one peer, with just one line of code you can fully intercept the entire connection, allowing you to easily observe all raw unencrypted network traffic, and inject or transform any WebRTC data or media en route.

I've been working on this over the last year (as one part of a projectopens in a new tab funded by EU Horizon's Next Generation Internet initiativeopens in a new tab) and building a framework called MockRTCopens in a new tab, which provides all the foundations needed to automatically intercept, inspect & mock WebRTC traffic for testing, network debugging & MitM proxying.

If that sounds cool and you just want to jump straight in and try it yourself, get started here: github.com/httptoolkit/mockrtc/opens in a new tab.

On the other hand, if you want to understand the gritty details of how this works and learn what you can do with it in practice, read on:

WebRTC, under the hood

Let's step back slightly here before we dive in. WebRTC is:

- A set of JavaScript APIs, available in web pages, that allows access to user media streams (microphones, webcams, screen sharing) and creation of peer-to-peer network connections.

- A set of network protocols, combined to allow reliable connection negotiation, setup and data streaming directly between peers on the public internet.

The web API part is relatively straightforward: you can access user media on the web using navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia() (with some permission prompts) to get a media stream, and you can create P2P connections by creating an RTCPeerConnection and using the methods there to connect to a remote peer.

Once the connection is set up, it can include any number of named data channels, carrying arbitrary messages between peers, and bidirection or unidirectional media streams carrying video or audio. Internally each can be carried over different independent transports with different properties - sending video over fast-but-unreliable UDP while messages travel over an ordering-guaranteed TCP connection, for example - or bundled together into multiplexed streams.

Before your connection gets to this happy state though, some relatively simple calls to the WebRTC JS API actually trigger a quite complex negotiation process by the browser(s) involved to agree and create the required network connections. This is complicated, in large part because they're trying to reliably set up secure peer-to-peer connections, on a modern internet where a very large number of peers are behind firewalls and NATopens in a new tab devices (like your home router), which block most inbound connections.

We don't need to get into the full details of how this works at a low level, but there is a common structure to connection setup - managed by the browser by coordinated via the exposed APIs - that it's useful to understand before we dig in into intercepting this.

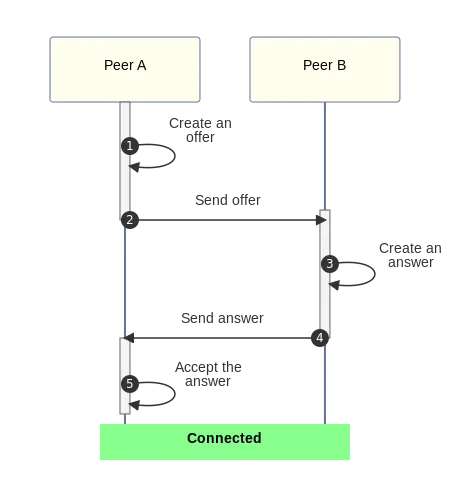

WebRTC connection setup

To do initial connection negotiation, WebRTC peers swap configurations in a format called SDP (Session description Protocol). This is a string, containing a series of lines like a=group:BUNDLE 0 1, which defines every connection parameter. That includes the available IP/port/protocol combinations to try connecting to, the video/audio codecs and extensions that will be used on each media stream, and the encryption keys and fingerprints used to authenticate & secure the connection.

There's a nice example & line-by-line breakdown of an SDP configuration hereopens in a new tab.

These configurations aren't swapped simultaneously: one peer sends an SDP 'offer', the other peer receives it, decides which proposed configuration parameters will work, and sends back a confirmatory SDP 'answer' with the agreed parameters, which the first peer receives & accepts to complete the connection.

The process of transferring the offer and answer here is called 'signalling', and is the one part of this process that isn't managed by the browser or fixed by the spec. Peers can share the connection configuration any way they like.

It's most common to share this via websocket connections through a central server both peers connect to, but you can also bootstrap a connection over a chat channel, or by manually by copying & pasting configuration between computers, or you could put it in a QR code on a series of postcards, tie it to a homing pigeon, you name it.

That bit is up to you, but all the other offer/answer generation and calculation work is generally handled for you by your browser automatically, such that the real code to swap an offer and answer looks something like:

// --- In one browser: --- const firstPeer = new RTCPeerConnection(); // ...here, first configure the media/data channels you want on the connection, then... const offer = firstPeer.createOffer(); await firstPeer.setLocalDescription(offer); sendOfferToSecondPeer(offer); // <-- How you do this signalling is up to you // --- In the other browser: --- const offer = receiveOfferFromFirstBrowser(); const secondPeer = new RTCPeerConnection(); secondPeer.setRemoteDescription(offer); const answer = secondPeer.createAnswer(); secondPeer.setLocalDescription(answer); sendAnswerBackToFirstPeer(answer); // --- Back in the first browser: --- const answer = receiveAnswerFromSecondPeer(); await firstPeer.setRemoteDescription(answer); // If all went well, both peers are now connected!

I am simplifying this a bit! Most notably there's an optional but widely used 'ICE candidate trickling' process that I'm omitting, where you immediately send your offer/answer without including full network address & port details, and then you 'trickle' over extra candidates later over your signalling channel as you discover them. But this basic offer/send/answer/receive flow is a good outline, and it's worth keeping this in mind as we continue.

Once this is done, both peers have agreed a set of connection details, media codecs & parameters and most relevantly encryption keys, and they can now talk happily over their peer-to-peer fully encrypted WebRTC connection, safe in the knowledge that nobody else can intercept or interfere with the contents of that.

Intercepting WebRTC

So, given all that, how can we intercept this, so once these connections are created we can see the data that's sent, and transform and inject our own traffic to mess with it?

Barring finding a major issue in a widely used security algorithm or cryptographic system, by design we're never going to be able to do this for an existing completed connection. That's good! Otherwise attackers would be able to do the same.

We can do this though if we can intercept the signalling traffic here. WebRTC connections are only as secure as their signalling channel, and so if we can easily provide our own configuration at the signalling stage, then we can change the connection certificates and network addresses agreed there at will.

By doing so, we can sit between two peers, tell both to connect to us instead of each other, and then we can forward traffic between the two any way we like.

Doing this in the general case is complicated - we'll get into those details in a second - but this is enough to let us start with the simplest use case: creating a mock peer to connect to directly in automated testing.

How to create a mock WebRTC peer in testing environments

In a web application test environment, you usually have direct control over signalling - you're often mocking setup processes & network traffic in other ways anyway - so in most setups it's easy to tweak your signalling setup to manually provide data for a remote peer who wants to connect. That means we can directly mock traffic to a single peer, which is often what you want to do for simple tests of WebRTC-based application.

To support this, MockRTC exposes APIs to define a mock WebRTC peer, preconfigure it with certain behaviours, and then get connection parameters you can directly drop into a signalling channel.

That looks something like this:

// --- In your test code: const mockPeer = await mockRTC.buildPeer() .waitForNextMessage() .thenSend('Goodbye'); // ^ This defines the rules of how the peer will behave const { offer, setAnswer } = await mockPeer.createOffer(); sendOfferToChannel(offer); // <-- Send the offer on your app's normal signalling channel // --- Do normal WebRTC setup in your application code: const offer = receiveOfferFromChannel(); const realPeer = new RTCPeerConnection(); realPeer.setRemoteDescription(offer); const answer = realPeer.createAnswer(); realPeer.setLocalDescription(answer); sendAnswerToChannel(answer); // --- Back in your test code: const answer = receiveAnswerFromChannel(); setAnswer(answer); // Your application being tested is now connected to the mock peer! // As soon as the real peer sends any message on a WebRTC data channel, it will // receive a 'Goodbye' message response, and the connection will close.

As seen here, MockRTC peers can be built with .buildPeer() followed by a series of step methods (to send messages, open channels, add delays, echo data and media and more). Once defined, you can call createOffer() or createAnswer() on them to get connection parameters that you can connect to with any real WebRTC peer.

Once you have a mock peer, it's possible to inspect every message it received with mockPeer.getAllMessages() and mockPeer.getMessagesOnChannel(channel), allowing you to verify the expected WebRTC traffic at the end of a test. It's also possible to actively monitor all WebRTC traffic, with events like mockRTC.on('data-channel-message-received', (event) => ...) or media track stats with mockRTC.on('media-track-stats', (event) => ...), to observe and log all traffic more generally across many connections.

If you want to try this out yourself, take a look at the getting started guideopens in a new tab.

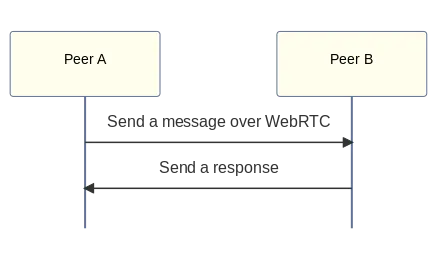

This is a neat demo, and useful for testing, but this isn't really interception, and no traffic is being proxied - it's just a convenient way to build test peers.

Fortunately we can extend this! Let's intercept real WebRTC traffic between two real unsuspecting peers.

How to intercept & debug WebRTC in a real browser environment

To intercept traffic between two peers, we need to go further, and inject our signalling configuration into both peers at once.

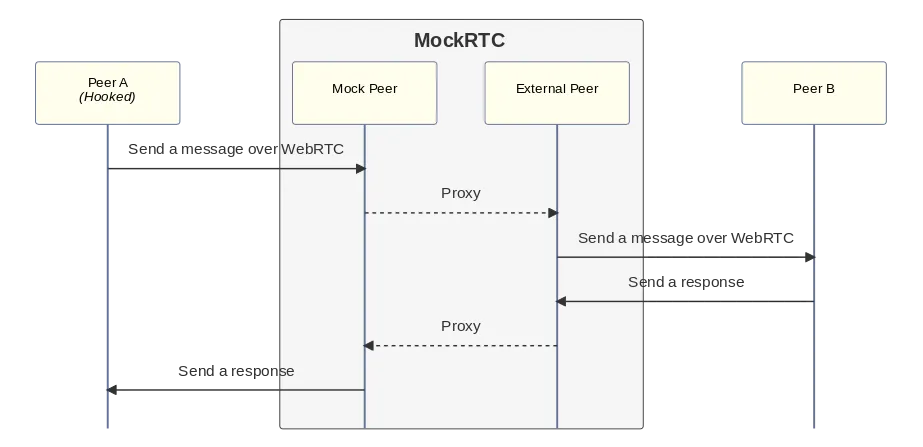

MockRTC can do this automatically, by using a set of JavaScript hooks in one peer's browser environment, which wrap the built-in WebRTC APIs to transparently redirect all traffic from both peers, making MockRTC a MitM WebRTC proxy. You can inject these JS hooks manually into your code (e.g. in a testing environment) or you can dynamically inject this into pages, e.g. via a web extension or similar (more on that later).

Using the provided hooks requires running one line of code in the target page of one peer:

// Redirect all traffic from one specific connection via a mock peer: MockRTC.hookWebRTCConnection(realConnection, mockPeer); // Call before negotiation // Or: redirect all WebRTC traffic in the entire page through a mock peer: MockRTC.hookAllWebRTC(mockPeer); // Call before creating connections

After running that, MockRTC will automatically transform normal WebRTC connections from this:

Into this:

I.e. redirecting traffic so that the hooked WebRTC peer always connects to a mock peer, instead of its real target, and remote peers are instead redirected to connect to an external peer, whose traffic can be dynamically proxied into the mock peer.

Once we're in this configuration, MockRTC is receiving and proxying all traffic unencrypted internally, and so can observe and modify it at will.

The hook logic that makes this work, in the case where the hooked peer offers first, looks something like this:

- Peer A creates an offer, by calling with

connection.createOffer()- MockRTC hooks this method. The hook creates a real offer for a real peer A connection (let's call this offer

AO) but passes it to MockRTC instead, then just storesAOand doesn't return it. - From

AO, MockRTC returns to the hook an equivalent offer, but for the external mock peer (EO) which we return from this method as if it was the real offer for this connection.

- MockRTC hooks this method. The hook creates a real offer for a real peer A connection (let's call this offer

- Peer A sends the offer to Peer B

- It thinks this is an offer to connect to itself (

AO) but it's actually an offer to connect to the external mock peer (EO).

- It thinks this is an offer to connect to itself (

- Peer B receives an offer and creates an answer (

BA)- This all happens remotely, for real with no hooks involved, but using the

EOoffer from the external mock peer.

- This all happens remotely, for real with no hooks involved, but using the

- Peer A receives the

BAanswer and accepts it withconnection.setRemoteDescription(answer)- MockRTC hooks this method, and passes the answer back to the external mock peer, which completes the external connection (connecting

BAwithEO). - The hook then sends the original real

AOoffer andBAanswer to MockRTC to create an equivalent answer (MA) - Once it receives it, it accepts that answer, completing the internal connection (connecting

AOtoMA)

- MockRTC hooks this method, and passes the answer back to the external mock peer, which completes the external connection (connecting

- The WebRTC connection is complete and usable for both real peers

- But we actually have two WebRTC connections, not one, and the MockRTC internally receives all traffic unencrypted, and can freely inspect it, proxy it, or transform it en route.

That's just one possible flow here, and so reality is a bit more complicated - if you're really interested, you can read the full hook definition here: https://github.com/httptoolkit/mockrtc/blob/main/src/webrtc-hooks.ts.

The end result though is that application code following the normal negotiation flow to connect to a real remote peer, send signalling over real channels to a real remote peer, ends up with a MitM'd connection through MockRTC that you can observe and control.

Once the connection is established, how exactly proxying works between the two MockRTC endpoints (the mock/external peers in the diagram above) is up to you, as it's defined by the peer's configured behaviour. For example:

const mockPeer = await mockRTC.buildPeer() .waitForNextMessage() // Wait for and drop the first datachannel message .send('Injected message') // Inject a message into the data channel .thenPassThrough(); // Then proxy everything else to the real peer

Traffic is only proxied between the mock & external peers at a passthrough step. That means that in this example, the hooked peer will receive nothing from the other real peer until they send a message (which won't be forwarded), then they'll receive 'Injected message', and then from there the connection will begin proxying as if it were a direct connection to the remote peer.

Just as when testing directly, we can also inspect all this traffic, so you can do totally transparent data channel inspection like so:

const mockPeer = await mockRTC.buildPeer() .thenPassThrough(); // Proxy everything transparently // Log all data channel traffic in both directions: MockRTC.on('data-channel-message-sent', ({ content }) => console.log('Sent:', content)); MockRTC.on('data-channel-message-received', ({ content }) => console.log('Received:', content)); // Or wait until later, then capture and log all messages at once: mockPeer.getAllMessages().then((message) => { console.log(message); });

Putting this into practice

Using the steps above, with the full documentationopens in a new tab for MockRTC, you can very quickly put this into practice to automated testing: either passing MockRTC's details directly through your own signalling mechanism, or using the MockRTC hooks and making real connections that are intercepted automatically.

For working testing examples, take a look at MockRTC's own integration tests, which create real WebRTC connections and then intercept & observe them in all sorts of fun ways: https://github.com/httptoolkit/mockrtc/tree/main/test/integration.

For testing use cases, this is very powerful, and immediately makes it possible to reach into the bowels of WebRTC and start observing and poking things. MockRTC is still very new, so the ways to observe and poke things are still limited, but all raw data is directly available internally as it's proxied, so observing and modifying anything is possible in theory, and suggestions or pull requests for new capabilities are very welcome! Just open your issues/PRs in the MockRTC repoopens in a new tab.

For more general use cases, like debugging all traffic from your browser live or building WebRTC proxy automation, you'll need to configure a mock peer and enable the hooks from inside the WebRTC client (your browser). MockRTC gives you all the tools to do so, but for now this does require some manual work (although there's another blog post coming very soon about HTTP Toolkit support to do this for you automatically...).

To get you started for now though, there's an example webextension project that you can clone, build & run to immediately test this out here: github.com/httptoolkit/mockrtc-extension-example/opens in a new tab. This is a barebones example that doesn't do much by itself, but will let you directly observe all data channel traffic from all tabs within the extension, and provides a base to add your own arbitrary logic, and monitor or rewrite WebRTC traffic in any way you like.

This is just the start, and there's more coming here soon! In the meantime, if you run into trouble or have questions, do please open an issueopens in a new tab or send me a message directly, and watch this space for more posts on deeper WebRTC integration in HTTP Toolkit itself...

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme within the framework of the NGI-POINTER Project funded under grant agreement No 871528.

Suggest changes to this pageon GitHubopens in a new tab