HTTP/3 has been in development since at least 2016, while QUIC (the protocol beneath it) was first introduced by Google way back in 2013. Both are now standardized, supported in 95% of users' browsersopens in a new tab, already used in 32% of HTTP requests to Cloudflareopens in a new tab, and support is advertised by 35% of websitesopens in a new tab (through alt-svc or DNS) in the HTTP Archive dataset.

We've developed a totally new version of HTTP, and we're on track to migrate more than 1/3 of web traffic to it already! This is astonishing progress.

At the same time, neither QUIC nor HTTP/3 are included in the standard libraries of any major languages including Node.js, Go, Rust, Python or Ruby. Curl recently gained supportopens in a new tab but it's experimental and disabled in most distributions. There are a rare few external libraries for some languages, but all are experimental and/or independent of other core networking APIs. Despite mobile networking being a key use case for HTTP/3, Android's most popular HTTP library has no supportopens in a new tab. Popular servers like Nginx have only experimental supportopens in a new tab, disabled by default, Apache has no support or published plan for support, and Ingress-Nginx (arguably the most popular Kubernetes reverse proxy) has dropped all plans for HTTP/3 supportopens in a new tab punting everything to a totally new (as yet unreleased) successor project instead.

Really it's hard to point to any popular open-source tools that fully support HTTP/3: rollout has barely even started.

This seems contradictory. What's going on?

I'm going to assume a basic familiarity with the differences between HTTP/1.1 (et al), HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 here. If you're looking for more context, http2-explainedopens in a new tab and http3-explainedopens in a new tab from Daniel Stenberg (founder & lead developer of curl) is an excellent guide.

Why do we need more than HTTP/1.1?

Let's step back briefly. Why does this matter? Who cares about whether HTTP/3 is being rolled out successfully or not? If browser traffic and the big CDNs support HTTP/3, do we even need it in other client or server implementations?

For example, one recent post argued there isn't much point to HTTP/2 past the load balanceropens in a new tab. To roughly summarize, their pitch is that HTTP/2's big benefits revolve around multiplexing to avoid latency issues & head-of-line blockingopens in a new tab, and these aren't relevant within a LAN or datacenter where round-trip time (RTT) is low and you can keep long-lived TCP connections open indefinitely.

You could make much the same argument for HTTP/3: this is useful for the high-latency many-requests traffic of web browsers & CDNs, but irrelevant elsewhere.

Even just considering HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2 though, the reality of multiplexing benefits is more complicated:

- Latency of responses isn't just network RTT: a slow server response because of server processing will block your TCP connection just as hard as network latency.

- Your load balancer is often not co-located with your backend, e.g. if you serve everything through a geographically distributed CDN, which serves most content from its cache, but falls back to a separate application server backend for dynamic content & cache misses.

- Long-lived TCP connections die. Networking can fail in a million ways, even within data centers, and 'keep-alive' is a desperate plea at best. Even HTTP itself will force this: there's cases like a response body failing half-way through that are unrecoverable in HTTP/1.1 without killing the connection entirely.

- Any spikes in traffic mean you'll end up with the wrong number of TCP connections one way or the other: either you need an enormous unused pool available at all times, or you'll need to open a flood of new connections as traffic spikes come in, and so deal with TCP slow start, RTT & extra TLS handshakes as you do so.

- There's a lot of traffic that's not websites and not just within in datacenters. Mobile apps definitely do have network latency issues, API servers absolutely do have slow endpoints that can block up open connections, and IoT is a world built almost exclusively of unreliable networks and performance challenges. All of these cases get value from HTTP/2 & HTTP/3.

Moving beyond multiplexing, there's plenty of other HTTP/2 benefits that apply beyond just load balancers & browsers:

- HTTP header compression (HPACKopens in a new tab and QPACKopens in a new tab in HTTP/2 & HTTP/3 respectively) makes for a significant reduction in traffic in many cases, especially on long-lived connections such as within internal infrastructure. This is useful on the web, but can be an even bigger boost on mobile & IoT scenarios where networks are limited and unrealiable.

- Bidirectional HTTP request & response streaming (only possible in HTTP/2 & HTTP/3) enables entirely different communication patterns. Most notably used in gRPC (which requires HTTP/2 for most usage) this means the client and server can exchange continuous data within the same 'request' at the same time, acting similarly to a websocket but within existing HTTP semantics.

- Both protocols support advanced prioritization support, allowing clients to indicate priority of requests to servers, to more efficiently allocate processing & receive the data they need most urgently. This is valuable for clients, but also between the load balancer and server: a cache miss for a waiting client has a very different priority to an optional background cache revalidation.

All that is just for HTTP/2. HTTP/3 improves on this yet further, with:

- Significantly increased resilience to unreliable networks. By moving away from TCP's strict packet ordering, HTTP/3 makes each stream within the connection fully independent, so a missed packet on one stream doesn't slow down another stream.

- Zero round-trip connection initialization. TLS1.3 allows zero round-trip connection setup when resuming a connection to a known server, so you don't need to wait for the TLS handshake before sending application data. For HTTP/1 & HTTP/2 though, you still need a TCP handshake first. With QUIC, you can do 0RTT TLS handshakesopens in a new tab, meaning you can connect to a server and send an HTTP request immediately, without waiting for a single packet in response, so there's no unnecessary RTT delay whatsoever.

- Reductions in traffic size, connection count, and network round trips that can result in reduced battery use for clients and reduced processing, latency & bandwidth for servers.

- Support for connection migrationopens in a new tab allowing a client to continue the same connection even as its IP address changes, and in theory even supporting multi-path connections using multiple addresses (e.g. a single connection to a server using both WiFi & cellular at the same time for extra bandwidth/reliability) in future.

- Improved network congestion handling by moving away from TCP: QUIC can use Bottleneck Bandwidth and RTTopens in a new tab (BBR) for improved congestion control via active detection of network conditions, includes timestamps in each packet to help measure RTT, has improved detection of and recovery from packet loss, has better support for explicit congestion notifications (ECN) to actively manage congestion before packet loss, and may gain forward-error correction (FEC) support in futureopens in a new tab too.

- Support for WebTransportopens in a new tab, a new protocol providing bidirectional full-duplex connections (similar to WebSockets) but supporting multiplexed streams to avoid head-of-line blocking, fixing various legacy WebSocket limitations (like incompatibility with CORS), and allowing streams to be unreliable and unordered - effectively providing UDP-style guarantees and lower-latency within web-compatible stream connections.

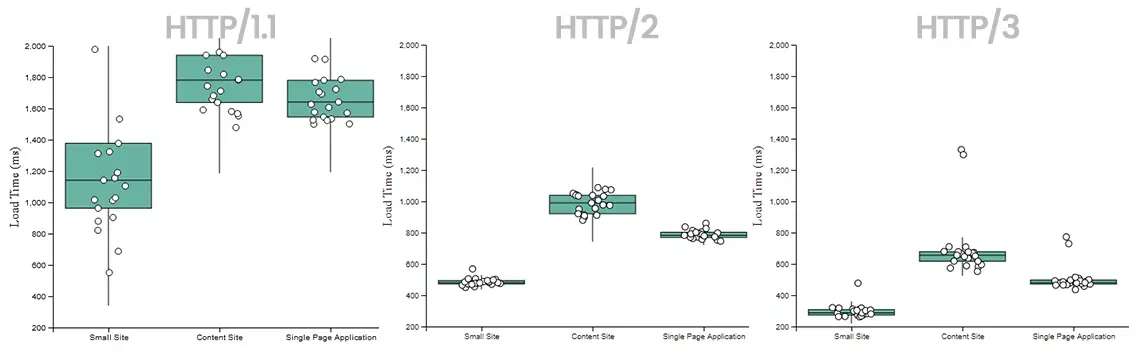

In addition to the theory, there's some concrete measureable benefits being reported already. RequestMetric ran some detailed benchmarksopens in a new tab showing some astonishing performance improvements for example:

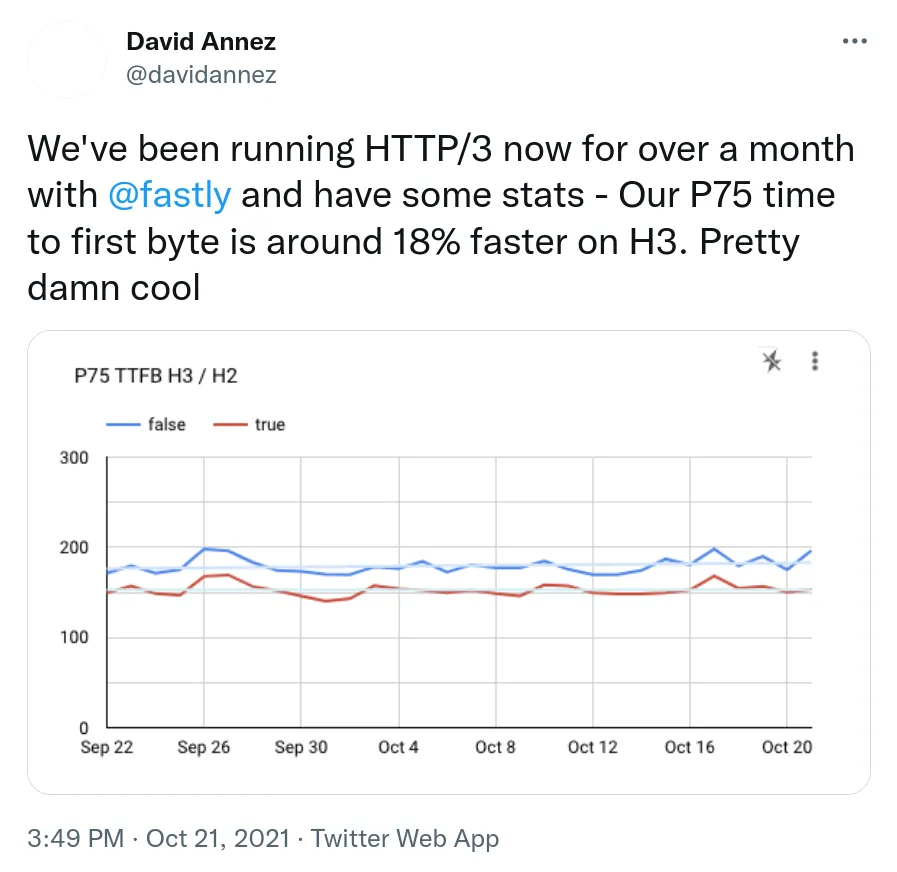

And Fastly shared the major improvements in time-to-first-byte they're seeing in the real world:

This all very clearly Good Stuff.

Now that the technology is standardized, widely supported in browsers & CDNs and thoroughly battle-tested, I think it's clear that all developers should be able to get these benefits built into their languages, servers & frameworks.

The two-tier web

That's not what's happened though: despite its benefits and frequent use in network traffic, most developers can't easily start using HTTP/3 end-to-end today. In this, HTTP/3 has thrown a long-growing divide on the internet into sharp relief. Nowadays, there's two very different kinds of web traffic:

- Major browsers plus some very-specific mobile app traffic, where a small set of finely tuned & automatic-updating clients talk to a small set of very big servers, with as much traffic as possible handled by either an enormous CDN (Cloudflare, Akamai, Fastly, CloudFront) and/or significant in-house infra (Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft).

- Everybody else: backend API clients & servers, every other mobile app, every smaller CDN, websites without a CDN, desktop apps, IoT, bots & indexers & scrapers, niche web browsers, self-hosted homelabs, CLI tools & scripts, students learning about network protocols, you name it.

Let's simplify a bit, and describe these two cases as 'hyperscale web' and 'long-tail web'. Both groups are building on the same basic standards, but they have very different focuses and needs, and increasingly different tools & platforms. This has been true for quite a while, but the reality of HTTP/3 makes it painfully clear.

There's a few notable differences in these groups:

- Long-tail traffic is bigger than the hyperscale traffic. 67%opens in a new tab of web page requests are served directly without a CDN, and of CDN traffic to Cloudflare in 2024, 30% is automated and 60% is API clientsopens in a new tab.

- The long-tail world is fragmented into different implementations, almost by definition. Most of the biggest implementations are open-source organizations with relatively little direct funding or full-time engineering power available, and much work is done by volunteers with no mandated central direction or clear focus.

- The hyperscale world is controlled by a relatively small number of key stakeholders on both client & server side (you can count the relevant companies without taking your socks off). This lets them agree standards to fit their needs quickly & effectively - literally putting a representative of every implementation in the same room.

- The hyperscale ecosystem has far more concentrated cash & motivations. It's a small number of players comprising some of the most valuable companies in the world, with business models that tie milliseconds of web performance directly to their bottom line.

- The long-tail is completely dependent on open-source implementations and shared code. If you want to build a new mobile app tomorrow, you obviously should not start by building an HTTP parser.

- The hyperscale ecosystem isn't worried about access to open-source implementations at all. They have sufficient engineering resources and complicated use cases that building their own custom implementation of a protocol from scratch can make perfect sense. Google.com is not going to be served by an Apache module with default settings, and Instagram is not sending requests with the same HTTP library as a Hello-World app.

- The combination of hyperscale's evergreen clients plus money & motivation plus tight links between implementers and the business using the tools, means they can move fast to quickly build, ship & iterate new approaches.

- Long-tail implementations are only updated relatively rarely (how many outdated Apache servers are there on the web?) and the maintainers are a tiny subset of the users, who care significantly about stability and avoiding breaking changes. Long-tail tool maintainers cannot just move fast and break things.

You can see the picture I'm painting. These two groups exist on the same web, but in very different ways.

Some of this might sound like the hyperscale gang are the nefarious baddies. That is not what I mean (fine, yes, there's an interesting conversation there more broadly, but talking strictly about network protocols here). Regarding HTTP/3 specifically, this is some superb engineering work that is solving real problems on the web, through some astonishingly tidy cooperation on open standards across different massive organizations. That's great!

There are many many people using services built by these companies, and their obsession with web performance is improving the quality of those services for large numbers of real people every day. This is very cool.

However, this would be much cooler if it was accessible to every other server, client & developer too. Most notably, this means the next generation of web technology is being defined & built by one minority group, and the larger majority have effectively no way to access this technology right now (despite years of standardization and development) other than paying money to the CDNs of that first minority group to help. Not cool.

OpenSSL + QUIC

I think the hyperscaler/long-tail divide is the fundamental cause here, but that's created quite a few more concrete issues downstream, the most notable of which is OpenSSL's approach to QUIC.

OpenSSL is easily the most used TLS library, and it's the foundational library for a large number of the open-source tools discussed above, so their support for this is essential to bringing QUIC & HTTP/3 to the wider ecosystem. There's already been quite a bit ofopens in a new tab extensiveopens in a new tab publicopens in a new tab discussionopens in a new tab aboutopens in a new tab OpenSSL's approach to QUIC, but as a quick summary:

- BoringSSL shipped a usable API for QUIC implementations back in 2018.

- OpenSSL did not, so various forks like QuicTLS appeared, providing OpenSSL plus BoringSSL's QUIC API.

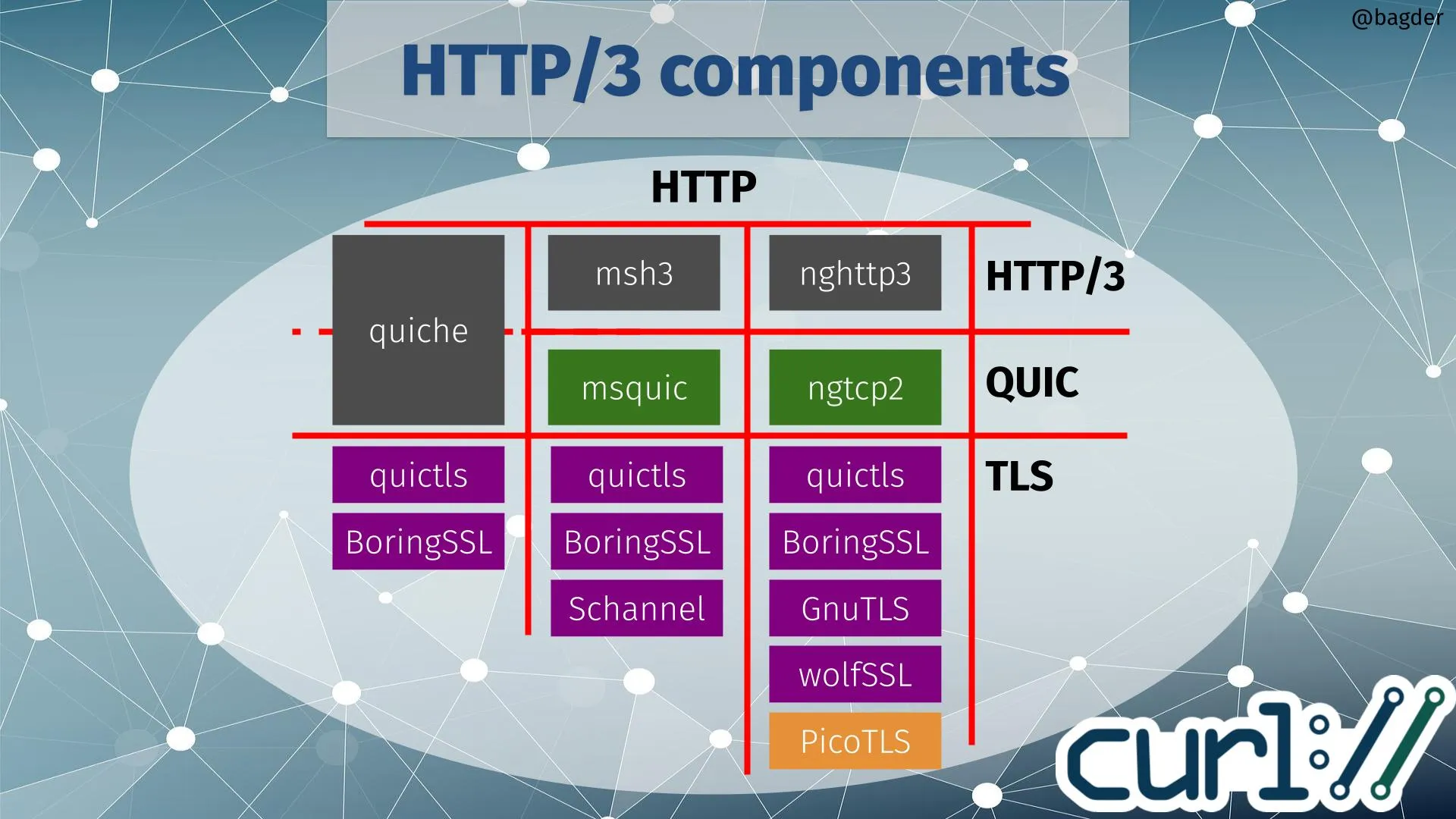

- An ecosystem of QUIC & HTTP/3 implementations (most notably Quiche, msh3/msquic, and nghttp3/ngtcp2) were built on top of BoringSSL and these forks over the many subsequent years.

- OpenSSL has since slowly implemented an incompatible approach that this ecosystem can't directly use, with client support released in OpenSSL 3.2 (2023), and server support landing imminently in OpenSSL 3.5 (2025).

Some would argue this is a major mistake by OpenSSL, while I think OpenSSL would argue that BoringSSL's design is flawed and/or unsuitable for OpenSSL, and it was worth taking the time to do it right.

Regardless of who's actually 'right', this has created a significant schism in the entire ecosystem. Curl has a good overview of the state of play excluding OpenSSL:

OpenSSL's approach doesn't work easily in the TLS section for any of the existing QUIC & HTTP/3 implementations. In effect, they've started another column, but with no compatible implementations currently available in the HTTP/3 & QUIC spots.

This is a notable issue because for most major projects it would be an enormous & problematic undertaking to drop support for OpenSSL, which effectively means they still cannot ship built-in QUIC support today. Node.js recently briefly discussedopens in a new tab even dropping OpenSSL entirely because of this, in favour of BoringSSL or similar, but it's clear that it's not practical: it would be an enormous breaking change, no alternative offers the same levels of long-term support guarantees, and Node and other languages are often shipped in enviroments like Linux distributions where it uses the system's shared OpenSSL implementation, so this would create big headaches downstream too.

This is one example of the difference in fundamental pressures of the two tiers of organizations on the web here: open-source tools can't break things like this, and the libraries available to the long-tail are fragmented and uncoordinated. Meanwhile hyperscalers can make decisions quickly and near-unilaterally to set up implementations that work for their environments today, allowing them to get the benefits of new technologies without worrying too much about the state of the open-source common ecosystem for everybody else.

What happens next?

I hope this makes it clear there's a big problem here: underlying organizational differences are turning into a fundamental split in technologies on the Internet. There's an argument that despite the benefits, the long-tail web doesn't need HTTP/3, so they can just ignore it, or use a CDN with built-in support if they really care, and there is no real obligation as such for the hyperscalers to provide convenient implementations to the rest of us just because they want to use some neat new tech between themselves.

The problem here though is that there are real concrete benefits to these technologies. QUIC is a significant improvement on alternatives, especially on slow or unreliable mobile internet (e.g. everywhere outside the well-connected offices of the developed world) and when roaming between connections. There are technologies built on top of it, like WebTransport which provides additional significant new features & performance to replace WebSockets. There will be more features that depend on HTTP/3 in future (see how gRPC built on HTTP/2 for example). Again: the technology here is great! But it's a challenge if those benefits are not evenly distributed, and only accessible to a small set of organizations and their customers.

Continuing down this road has some plausible serious consequences:

- In the short term, the long-tail web gains a concerete disadvantage vs the hyperscale web, as HTTP/3 and QUIC makes hyperscale sites faster & more reliable (especially on slow & mobile internet).

- Other web tools and components (React et al) used by developers either working for hyperscale organizations or building on top of their tools & infra will increase in complexity to match, taking HTTP/3's benefits for granted and moving forwards on that basis, making them less and less relevant to other use cases.

- If we're not careful, the split between the long-tail & hyperscale cases will widen. New features & tools for each use case will emerge, and won't be implemented by the other, and tooling will increasingly stratify.

- If hyperscale-only tech is widespread but implementations are not, it becomes increasingly difficult to build tools to integrate with these. Building a Postman-like client for WebTransport is a whole lot harder if you're implementing the protocol from scratch instead of just a UI.

- You'll start to see lack of HTTP/3 support used as a signal to trigger captchas & CDN blocks, like as TLS fingerprinting is already today. HTTP/3 support could very quickly & easily become a way to detect many non-browser clients, cutting long-tail clients off from the modern web entirely.

- As all this escalates and self-reinforces, it becomes less & less sensible for the hyperscale side to worry about the long-tail's needs at all, and the ecosystem could stratify completely

All of that is a way away, and quite hypothetical! I suspect some of this will happen to some degree, but there's a wide spectrum of possibility. It's notable though that this doesn't just apply to HTTP/3: the centralization and coordination of a few CDN & web clients like this could easily play out similarly in many other kinds of technological improvements too.

For HTTP/3 at least, I'm hopeful that there will be a happy resolution here to improve on this split in time, although I don't know if it will come soon enough to avoid notable consequences. Many of the external libraries and experimental implementations of QUIC & HTTP/3 will mature with time, and I think eventually (I really really hope) the OpenSSL QUIC API schism will get resolved to open the door to QUIC support in the many OpenSSL-based environments, either with adapters to support both approaches or via a new HTTP/3 & QUIC stack that supports OpenSSL model directly. If you're interested in working on either, and there's anything I can do to help directly or to help fund that work, please get in touchopens in a new tab.

None of that will happen today though, so unfortunately if you want to use HTTP/3 end-to-end in your application, you may in for a hard time for a while yet. Watch this space.

Want to debug HTTP/1 and HTTP/2 in the meantime? Test out HTTP Toolkitopens in a new tab now. Open-source one-click HTTP(S) interception & debugging for web, Android, terminals, Docker & more.

Suggest changes to this pageon GitHubopens in a new tab