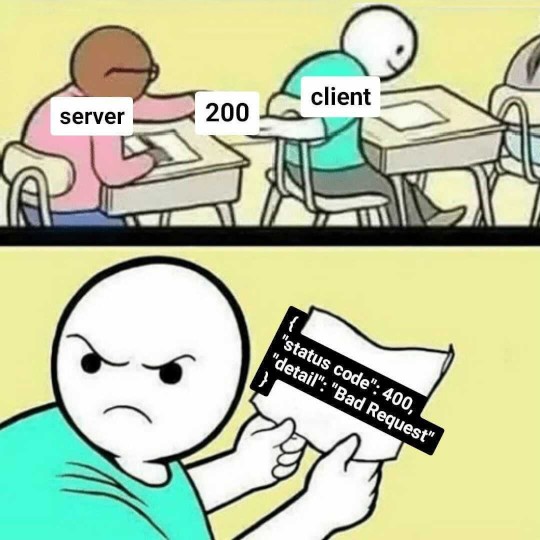

When an API request doesn't work, hopefully the client receives a sensible HTTP error status, like 409 or 500, which is a good start. Unfortunately though, whilst 400 Bad Request might be enough to know who's at fault, it's rarely enough information to understand or fix the actual problem.

Many APIs will give you more details in the response body, but sadly each with their own custom style, varying between APIs or even between individual endpoints, requiring custom logic or human intervention to understand.

This is not inevitable. Suspend disbelief with me for a second. Imagine a better world, where instead every API returns errors in the same standard format.

We could have consistent identifiers to recognize types of errors, and clear descriptions and metadata easily available, everywhere. Your generic HTTP client could provide fine-grained details for any error automatically, your client error handling could easily & reliably differentiate specific errors you care about, and you could handle common errors across many different APIs with one set of shared logic.

RFC 7807opens in a new tab from the IETF is a proposed standard aiming to do exactly this, by defining a standard format for HTTP API error responses. It's seeing real-world usage already, it's easy to start supporting in existing APIs and clients, and it's well worth a look for everybody who builds or consumes HTTP APIs.

Why is a standard error format useful?

Let's step back a little. One key feature of HTTP is the use of standard response status codes, like 200 or 404. When used correctly, these ensure that clients can automatically understand the overall status of a response, and take appropriate action based on that.

Status codes are especially great for error handling. Rather than requiring custom rules to parse & interpret every response everywhere, almost all standard HTTP clients will throw an error automatically for you when a request receives an unexpected 500 status, and this ensures that unexpected errors get reliably reported and can be handled everywhere easily.

This is great, but it's very limited.

In practice, an HTTP 400 response might mean any of the below:

- Your request is in the wrong format, and couldn't be parsed

- Your request was unexpectedly empty, or missing some required parameters

- Your request was valid but still ambiguous, so couldn't be handled

- Your request was valid, but due to a server bug the server thinks it wasn't

- Your request was valid, but asked for something totally impossible

- Your request was initiated, but the server rejected a parameter value you provided

- Your request was initiated, but the server rejected every parameter value you provided

- Your request was initiated, but the card details included were rejected by your bank

- Your request completed a purchase, but some other part of your request was rejected at a later stage

Those are all errors, they're all plausibly 400 errors triggered by a 'bad' request, but they're very different.

Status codes help differentiate error & success states, but don't go much further. Because of this, HTTP client libraries can't include any kind of useful details in thrown errors, and every API client has to write custom handling to parse each failing response and work out the possible causes and next steps for itself.

Wouldn't it be nice if the exception message thrown automatically by a failing HTTP request was Credit card number is not valid, rather than just HTTP Error: 400 Bad Request?

With a standard format for errors, each of the errors above could have their own unique identifier, and include standard descriptions and links to more details. Given that:

- Generic tools could parse and interpret error details for you, all without knowing anything about the API in advance.

- APIs could more safely evolve error responses, knowing that error type identifiers ensure clients will still consistently recognize errors even if explanation messages change.

- Custom API clients could check error types to handle specific cases easily, all in a standard way that could work for every API you use, rather than requiring a from-scratch API wrapper and epic boss fight against the API documentation every. single. time.

What's the proposed error format?

To do this, RFC7807 proposes a set of standard fields for returning errors, and two content types to format this as either JSON or XML.

The format looks like this:

{ "type": "https://example.com/probs/out-of-credit", "title": "You do not have enough credit.", "detail": "Your current balance is 30, but that costs 50.", "instance": "/account/12345/transactions/abc" }

or equivalently, for XML:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <problem xmlns="urn:ietf:rfc:7807"> <type>https://example.com/probs/out-of-credit</type> <title>You do not have enough credit.</title> <detail>Your current balance is 30, but that costs 50.</detail> <instance>/account/12345/transactions/abc</instance> </problem>

These RFC defines two new corresponding content types for these: application/problem+json or application/problem+xml. HTTP responses that return an error should include the appropriate content type in their Content-Type response header, and clients can check that header to confirm the format.

This example includes a few of the standardized fields defined by the spec. The full list is:

type- a URI that identifies the type of error. Loading the URI in a browser should lead to documentation for the error, but that's not strictly required. This field can be used to recognize classes of error. In future, in theory, sites could even share standardized error URIs for common cases to allow generic clients to detect them automatically.title- a short human-readable summary of the error. This is explicitly advisory, and clients must usetypeas the primary way to recognize types of API error.detail- a longer human-readable explanation with the full error details.status- the HTTP status code used by the error. This must match the real status, but can be included here in the body for easy reference.instance- a URI that identifies this specific failure instance. This can act as an id for this occurrence of the error, and/or a link to more detail on the specific failure, e.g. a page showing the details of a failed credit card transaction.

All of these fields are optional (although type is highly recommended). The content types are allowed to include other data freely, as long as they don't conflict with these fields, so you can add your own error metadata here too, and include any other data you'd like. Both instance and type URIs can be either absolute or relative.

The idea is that:

- APIs can easily indicate that they're following this standard, by returning error responses with the appropriate

Content-Typeheader. - This is a simple set of fields you could easily add on top of most existing error responses, if they're not already present.

- Clients can easily advertise support and thereby allow for migration, if necessary, just by including an

Accept: application/problem+json(and/or+xml) header in requests. - Client logic can easily recognize these responses, and use them to dramatically improve both generic and per-API HTTP error handling.

How do I start using this?

Right now, this is a proposed standard, so it's not yet widespread, and in theory it may change.

That said, it's already use in many places, including serious things like 5G standardsopens in a new tab, and there's convenient tools available for most languages and frameworks, including:

- Built-in support in ASP.NETopens in a new tab

- Genericopens in a new tab and Expressopens in a new tab libraries for Node.js

- Genericopens in a new tab and Spring Web MVCopens in a new tab libraries for Java

- Genericopens in a new tab and Django REST APIopens in a new tab libraries for Python

- Genericopens in a new tab, Railsopens in a new tab and Sinatraopens in a new tab libraries for Ruby

- Genericopens in a new tab and Symfonyopens in a new tab libraries for PHP

- Libraries for Rustopens in a new tab, Goopens in a new tab, Scalaopens in a new tab, Haskellopens in a new tab...

So it's pretty widespread already in most major ecosystems, it's here to stay, and it's time for the next step: spreading usage in APIs & clients until we reach a critical mass where most API errors are formatted consistently like this, it becomes a default everywhere, and we can all reap the benefits.

How do we do that?

If you're building or maintaining an API:

- Try to return your errors in RFC 7807opens in a new tab format with the appropriate

Content-Typeresponse header, if you can. - If you already have an error format, which you need to maintain for compatibility, see if you can add these fields on top, and extend it to match the standard.

- If you can't, try detecting support in incoming

Acceptheaders, and using that to switch your error format to the standard where possible. - File bugs with your API framework (like this oneopens in a new tab) suggesting they move towards standard error formats in future.

If you're consuming an API:

- Check error responses for these content types, and improve your error reporting and handling by using the data provided there.

- Consider including an

Acceptheader with these content types in your requests, to advertise support and opt into standard errors where they're available. - Complain to APIs you use that don't return errors in this standard format, just as you would for APIs that didn't bother returning the right status codes.

And everybody:

- Get involved! This is a spec under the umbrella of the new "Building Blocks for HTTP APIs" working group at the IETF. You can join the mailing listopens in a new tab to start reading and getting involved with discussions around this and other specs for possible API standards, from rate limitingopens in a new tab to API deprecationsopens in a new tab.

- Spread the word to your colleagues and developer friends, and help make errors a little bit easier to handle for everybody.

Debugging APIs or HTTP clients, and want to inspect, rewrite & mock live traffic? Try out HTTP Toolkitopens in a new tab right now. Open-source one-click HTTP(S) interception & debugging for web, Android, servers & more.

Suggest changes to this pageon GitHubopens in a new tab